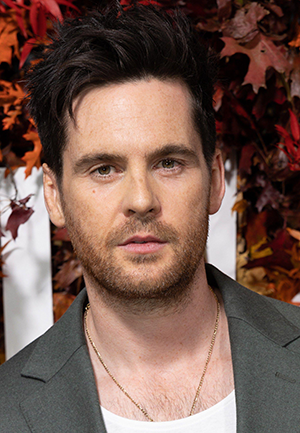

A brilliant new interview with Tom has been posted on The Gothamist website, where he discusses Arcadia on Broadway, New York and all night ping pong. Tom also explains how they have overcome the earlier audio problems found in previews. Read the full interview on the website.

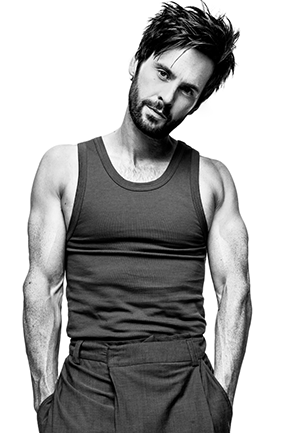

Arcadia, is currently enjoying a well-received revival at the Barrymore theater. Tom Riley, the 30-year-old British actor making his Broadway debut in the production as the 19th-century poet, tutor to a genius and lothario Septimus Hodge, talked with us about sound amplification on Broadway, Tom Stoppard's way with words, working with the actor who originated your role on Broadway, and why they really need you to turn off your cell phone before the show (hint: a remote-controlled tortoise is involved).

Even in straight plays these days it feels pretty rare to see mic-less production Broadway. Did you find that that changes how quickly the audience gets pulled into the show?

It can do. The thing is, we had some problems with the set during previews, which was no secret. We were out there trying very hard to get across these complicated, complex lines that were echoing within the set, within the auditorium. A lot of the ends of our lines and consonants were vanishing, which makes it of course hard to understand. But that's since been fixed. They actually put some downstage mics on the front of the stage, and speakers in the areas of the auditorium where people were missing bits, so we managed to kill that problem, fortunately. For the first few weeks, it was certainly something we had to take into account, slowing down and being clearer, because we didn't realize that the auditorium would be so echo-y.

And you've said you'll sometimes change your diction depending on how the audience responds. Is that still the case?

It can be, yeah. There are certain things where, you just—because of the nature of the play and the nature of some of the writing, if a line is missed then a whole scene will lose some of it's power later on in the show because the audience simply didn't hear it. So you get used to understanding—when I say didn't hear it, that's probably not right. Rather, didn't understand it's importance at the time of it being said. You become aware of which lines to take care of in order to make sure the story comes across as clearly as it can.

In a play of this nature, there are always bits that are going to fly over people's heads—including us at the beginning. We spent however many weeks picking it apart and making sense of it and knowing it inside out, and therefore taking on the responsibility to make sure the audience does, as well.

Much has been made in the press—it is an easy thing to hook on to, over the fact that Billy Crudup played Septimus in the original Broadway production and Raul Esparza has played Septimus previously. Has that effected your performance at all?

The only time where I felt the pressure of it really was the read-through, at the beginning, where I thought, These two incredible actors have both said these lines before me and have had a whole rehearsal period before me to get it right and I'm coming in to a read-through completely fresh. But they are such gracious people, both of them, that neither of them in any way suggested things I could do or made comments even. They were just extremely supportive and complimentary, which made it such an easier place to be. Knowing they were there should I get in a pickle and should I be stuck with it, I had someone I could go to: Now what did you do, this is a roadblock for me. At the same time, they weren't forcing themselves on me. It made for a more supportive atmosphere, a safer atmosphere, than perhaps even what I expected.

So I was wrongly under the impression you were in the London production too.

No, no, I wasn't. They decided when they did it over here just to completely re-cast. I don't know if they were struggling to find a few extra characters, but they decided to do a week in London and I just went in for that. This is my first time as much as everyone else.

Did Tom Stoppard work with you at all?

He did, he was in for the whole first week. He came in and answered every question we had about the play and people's motivations. Even the simplest things: "Why am I saying this line to this character at this time?" through to "What is Fermat's last theorem and why is it relevant here?" He managed to sort of pick apart the quantum mechanics and the most basic relationship dynamics. So having him right at the beginning was amazing. Then he went away for three weeks and came back again just as we began previews to add a few notes here and there—through David [Levaux], never directly. He would sit with us during the note sessions but David would communicate everything Tom had suggested. It was great, having him there.

Of course what's terrifying about Tom is that he speaks like the play is written. So you sit there thinking, If I try to bring up my opinion here and you reply with this perfectly crafted sentence that manages to pack in wit and language like I've never heard, I'm going to feel like a fool! So you plan what you're going to say to him for a while so you don't sit there with egg on your face.

It's not very often that you get to work with a living playwright who's works are being taught seriously in schools.

No, absolutely. I studied him at university. It's incredible, I've been really lucky because I work with people like David Hare and Caryl Churchill and all who were playwrights I studied at uni. And to suddenly be in a room with them and have their direct opinions on the things that I sat, you know, in a seminar with a tutor and tried to pick apart, and just go, What was the author saying here? It was an English Lit major's dream.

So you were an English Lit major? I was, yeah.

Have there been any decisions you've made where you've gone against what Stoppard was suggesting?

That's what's interesting—I don't know if it's because he wrote it so long ago, and I know that fifteen years ago he was so hands-on with the fact that university lecturers came in to describe to the cast the most basic foundation of the theories being discussed, and he would give notes directly. And he says now, fifteen years later, he doesn't quite feel so protective of the text because he has said he's come to learn that actually the actors can occasionally bring things that he can't see that add to the writing. And when they do go too far away from him, he has David who's come to it to say, "No, bring it back."

No, I certainly haven't gone against anything he says, because everything he has had to say has been enlightening. But there were certain things we collaborated on coming to a conclusion with, for sure.

Anybody have dibs on that turtle when you're done with the show?

I hope someone takes that turtle and throws it out a window [laughing]. The problem is, because it is remote-controlled—oh, I'm technically not supposed to say that, but it is a remote-controlled turtle—it occasionally malfunctions depending on whether or not people keep their phones on in the auditorium. So if everyone just switches their phone to silent, once in a while...I mean, we had a performance about three nights ago where the turtle's head just went in and out in and out in and out [makes a funny noise] for that whole first scene...we were just all up there thinking, "Well, there's no way we're the most interesting thing on stage."

Couldn't you get up and turn it around?

You want to, but the legs were going in and out of the back, as well! The problem with all the props in Arcadia, if you mess with them, if one is forgotten, they are so important for the next scene, someone else will pick them up and use them, that you can't afford to mess with them. So I was just thinking, I wanted to take the tortoise off with me, but if I do, then Raul won't be able to pick it up in the next scene, and he'll be stuck..So you just have to force it on while feeling that at least the first five rows are watching the turtle.

Hopefully it will be back tonight and will be working!

You IMBD profile shows you've done a lot of television work in England—any plans to do TV here, since every other British actor seems to?

Well, I did a pilot for ABC a few years ago and it didn't get picked up. A fascinating experience. The money that's spent over here on network TV! But my feeling has always been, occasionally my agents here will say, "Do you want to come and work in America or do this in America," and actually I don't really care where I am if the work is good.

Well aren't they remaking Lost in Austen

Yeah, well that's been written. The script is finished for that as the movie, Sam Mendes is producing.

I love that one—that has been such an incredible, that was such an amazing thing in my career, that made me wonderful fans. People all over the world write letters about it still. To this day, it's being shown in Australia or New Zealand or Japan or Sweden...they just love the show. When we were making it we thought we were doing something quite good but we didn't quite realize it would have this incredible cult following.

Have you had a chance between all the rehearsal and your eight performances a week to do anything around town?

Yeah, I've been all over, because the best thing about being out here is that my friends have taken the chance to get out here and join me because it's a good excuse for a holiday. And I've had a huge list of recommendations from friends...in the last few nights I've been to Spin, the all-night ping-pong table tennis place on 23rd street. I've been to Brooklyn Bowl. In New York, the show comes down here and that's not the end of the evening. We're finishing at 11 o'clock and the night is still relatively young in New York. In London, it's supposed to be a 24-hour town but technically after one o'clock everyone goes home. I love the East Village and the LES—I love this area. I've had a great time.